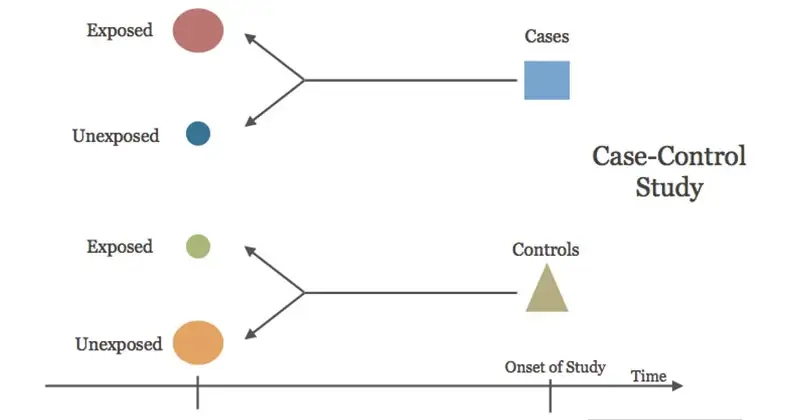

A case-control study (also known as a case-referent study) is a type of observational study in which two existing groups differing in outcome are identified and compared on the basis of some supposed causal attribute.

- It is designed to help determine if an exposure is associated with an outcome (i.e., disease or condition of interest). In recent years, the case-control approach has emerged as a permanent method of epidemiological investigation.

- Case-control studies are often used to identify factors that may contribute to a medical condition by comparing subjects who have that condition/disease (the “cases”) with patients who do not have the condition/disease but are otherwise similar (the “controls”).

- In theory, the case-control study can be described simply. First, identify the cases (a group known to have the outcome) and the controls (a group known to be free of the outcome). Then, look back in time to learn which subjects in each group had the exposure(s), comparing the frequency of the exposure in the case group to the control group.

- This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is the odds ratio (OR).

Source: EBM Consult, LLC

Interesting Science Videos

The Nature of Case-Control Studies

- By definition, a case-control study is always retrospective because it starts with an outcome then traces back to investigate exposures. When the subjects are enrolled in their respective groups, the outcome of each subject is already known by the investigator. This, and not the fact that the investigator usually makes use of previously collected data, is what makes case-control studies ‘retrospective’.

- The case-control study compares the prevalence of suspected causal factors between individuals with disease and controls who do not have the disease. If the prevalence of the factor is significantly different in cases than it is in controls, this factor may be associated with the disease.

- Although case-control studies can identify associations, they do not measure risk. An estimate of relative risk, however, can be derived by calculating the odds ratio.

- The case-control method has three distinct features:

- both exposure and outcome (disease) have occurred before the start of the study

- the study proceeds backward from effect to cause; and

- it uses a control or comparison group to support or refute an inference.

Steps Involved in Case-Control Studies

- By definition, a case-control study involves two populations – cases and controls.

- The focus is on a disease or some other health problem that has already developed.

- Case-control studies are basically comparison studies. Cases and controls must be comparable with respect to known “confounding factors” such as age, sex, occupation, social status, etc.

- The questions asked relate to personal characteristics and antecedent exposures which may be responsible for the condition studied.

- For example, one can use as “cases” the immunized children and use as “controls” un-immunized children and look for factors of interest in their past histories.

There are four basic steps in conducting a case-control study:

- Selection of cases and controls

- Matching

- Measurement of exposure, and

- Analysis and interpretation

A. Selection of Cases and Controls

- The first is to identify a suitable group of cases and a group of controls.

- While the identification of cases is relatively easy, the selection of suitable controls may present difficulties.

- The definition of what constitutes a “case” is crucial to the case-control study.

- It involves two specifications:

- DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA: The diagnostic criteria of the disease and the stage of the disease, if any (e.g., breast cancer Stage I) to be included in the study must be specified before the study is undertaken. Once the diagnostic criteria are established, they should not be altered or changed until the study is over.

- ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA: The second criterion is that of eligibility. A criterion customarily employed is the requirement that only newly diagnosed (incident) cases within a specified period of time are eligible than old cases or cases in advanced stages of the disease (prevalent cases).

- The cases may be drawn from hospitals or the general population.

- The cases should be fairly representative of all cases in the community.

- The controls must be free from the disease under study.

- They must be as similar to the cases as possible, except for the absence of the disease under study.

- As a rule, a comparison group is identified before a study is done, comprising of persons who have not been exposed to the disease or some other factor whose influence is being studied.

- Difficulties may arise in the selection of controls if the disease under investigation occurs in subclinical forms whose diagnosis is difficult.

- Selection of an appropriate control group is, therefore, an important prerequisite, for it is against this, we make comparisons, draw inferences and make judgments about the outcome of the investigation.

- The possible sources from which controls may be selected include hospitals, relatives, neighbors and the general population.

- If many cases are available, and a large study is contemplated, and if the cost to collect case and control is about equal, then one tends to use one control for each case. If the study group is small (say under 50) as many as 2,3, or even 4 controls can be selected for each study subject.

- To sum up, the selection of proper cases and controls is crucial to the interpretation of the results of case-control studies.

B. Matching

- The controls may differ from the cases in a number of factors such as age, sex, occupation, social status, etc.

- An important consideration is to ensure comparability between cases and controls. This involves what is known as “matching”.

- Matching is defined as the process by which we select controls in such a way that they are similar to cases with regard to certain pertinent selected variables (e.g., age) which are known to influence the outcome of the disease and which, if not adequately matched for comparability, could distort or confound the results.

- While matching it should be borne in mind that the suspected aetiological factor or the variable we wish to measure should not be matched, because, by matching, its aetiological role is eliminated in that study. The cases and controls will then become automatically alike with respect to that factor.

- There are several kinds of matching procedures such as group matching, pair matching, etc.

C. Measurement of Exposure

- Definitions and criteria about exposure (or variables which may be of aetiological importance) are just as important as those used to define cases and controls.

- Information about exposure should be obtained in precisely the same manner both for cases and controls.

- This may be obtained by interviews, by questionnaires or by studying past records of cases such as hospital records, employment records, etc.

- It is important to recognize that when case-control studies are being used to test associations, the most important factor to be considered, even more, important than the P. values obtained, is the question of “bias” or systematic error which must be ruled out.

D. Analysis

The final step is analysis, to find out:

- Exposure rates among cases and controls to suspected factor.

- Estimation of disease risk associated with exposure (Odds ratio).

Advantages of Case-Control Studies

- Relatively easy to carry out.

- Rapid and inexpensive (compared with cohort studies).

- Require comparatively few subjects.

- Particularly suitable to investigate rare diseases or diseases about which little is known. But a disease which is rare in the general population (e.g., leukemia in adolescents) may not be rare in the special exposure group (e.g. prenatal X-rays).

- No risk to subjects.

- Allows the study of several different aetiological factors (e.g., smoking, physical activity and personality characteristics in myocardial infarction).

- Risk factors can be identified. Rational prevention and control programs can be established.

- No attrition problems, because case-control studies do not require follow-up of individuals into the future.

- Ethical problems are minimal.

Limitations of Case-Control Study

- Problems of bias relies on memory or past records, the accuracy of which may be uncertain; validation of information obtained is difficult or sometimes impossible.

- Selection of an appropriate control group may be difficult.

- We cannot measure incidence, and can only estimate the relative risk.

- Do not distinguish between causes and associated factors.

- Not suited to the evaluation of therapy or prophylaxis of disease.

- Another major concern is the representativeness of cases and controls.

- A hypothesis is necessary for case-control studies. Relationships will be observed only for those factors studied.

- Case-control studies are not useful for determining the spectrum of health outcomes resulting from specific exposures, because a definition of a case is required in order to do a case-control study.

References

- Gordis, L. (2014). Epidemiology (Fifth edition.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

- White, F., Stallones, L., & Last, J. M. (2013). Global public health: Ecological foundations. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Park, K. (n.d.). Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1706071/

- https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/epidemiology-uninitiated/8-case-control-and-cross-sectional

- https://www.students4bestevidence.net/case-control-and-cohort-studies-overview/