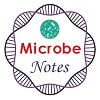

An epidemic is the rapid spread of infectious diseases to a large number of people in a given population within a short period of time.

- According to modern concepts, an epidemic is defined as the occurrence in a community or region of cases of an illness or other health-related events clearly in excess of normal expectancy.

- The community or region, and the time period in which the cases occur are specified precisely.

- An epidemic disease is not required to be contagious, and the term has been applied to West Nile fever and the obesity epidemic (e.g. by the World Health Organization), among others.

- Thus, epidemics refer to the “unusual” occurrence in a community or region of disease, specific health-related behavior (e.g., smoking) or other health-related events (e.g., traffic accidents) clearly in excess of “expected occurrence”.

- The number of cases varies according to the disease-causing agent, and the size and type of previous and existing exposure to the agent.

Causes of Epidemics

Epidemics of infectious disease are generally caused by several factors including:

- Change in the ecology of the host population (e.g. increased stress or increase in the density of a vector species)

- Genetic change in the pathogen reservoir or the introduction of an emerging pathogen to a host population (by the movement of pathogen or host).

- Generally, an epidemic occurs when host immunity to either an established pathogen or newly emerging novel pathogen is suddenly reduced below that found in the endemic equilibrium and the transmission threshold is exceeded.

- The conditions which govern the outbreak of epidemics also include infected food supplies such as contaminated drinking water and the migration of populations of certain animals, such as rats or mosquitoes, which can act as disease vectors.

- Certain epidemics occur at certain seasons. For example, whooping-cough occurs in spring, whereas measles produces two epidemics, one in winter and one in March. Influenza, the common cold, and other infections of the upper respiratory tract, such as sore throat, occur predominantly in the winter.

- Disease outbreaks are usually caused by an infection, transmitted through person-to-person contact, animal-to-person contact, or from the environment or other media.

- Outbreaks may also occur following exposure to chemicals or to radioactive materials. For example, Minamata disease is caused by exposure to mercury.

- Epidemics may be the consequence of disasters of another kind, such as tropical storms, floods, earthquakes, droughts, etc.

- Occasionally the cause of an outbreak is unknown, even after thorough investigation.

Types of Epidemics

Two major types of epidemics may be distinguished.

A. Common-Source Epidemics

- Common-source epidemics are frequently, but not always, due to exposure to an infectious agent.

- They can result from contamination of the environment (air, water, food, soil) by industrial chemicals or pollutant.

- Eg., Bhopal gas tragedy in India and Minamata disease in Japan resulting from consumption of fish containing a high concentration of methyl mercury.

(a) Single exposure or “point-source” epidemics:

- These are also known as “point-source” epidemics.

- The exposure to the disease agent is brief and essentially simultaneous, the resultant cases all develop within one incubation period of the disease.

- Eg., an epidemic of food poisoning

- The main features of a “point-source” epidemic are :

- The epidemic curve rises and falls rapidly, with no secondary waves

- The epidemic tends to be explosive, there is a clustering of cases within a narrow interval of time, and

- More importantly, all the cases develop within one incubation period of the disease.

(b) Continuous or multiple exposure epidemics:

- If the epidemic continues over more than one incubation period, there are either a continuous or multiple exposures to a common source or a propagated spread.

- Sometimes the exposure from the same source may be prolonged – continuous, repeated or intermittent – not necessarily at the same time or place.

- For example. a prostitute may be a common source in a gonorrhea outbreak, but since she will infect her clients over a period of time there may be no explosive rise in the number of cases. A well of contaminated water, or a nationally distributed brand of vaccine (e.g. polio vaccine), or food, could result in similar outbreaks.

- In these instances, the resulting epidemics tend to be more extended or irregular.

- The outbreak of respiratory illness, the Legionnaire’s disease, in the summer of 1976 in Philadelphia (USA) was a common-source, continuous or repeated exposure outbreak.

- This outbreak, as in other outbreaks of this type, continued beyond the range of one incubation period. There was no evidence of secondary cases among persons who had contact with ill persons.

B. Propagated Epidemics

- A propagated epidemic is most often of infectious origin and results from person-to-person transmission of an infectious agent (e.g., epidemics of hepatitis A and polio).

- The epidemic usually shows a gradual rise and tails off over a much longer period of time.

- Transmission continues until the number of susceptibles is depleted or susceptible individuals are no longer exposed to infected persons or intermediary vectors.

- The speed of spread depends upon herd immunity, opportunities for contact and secondary attack rate.

- Propagated epidemics are more likely to occur where a large number of susceptibles are aggregated, or where there is a regular supply of new susceptible individuals (e.g., birth, immigrants) lowering herd immunity.

C. Mixed Epidemics

- Some epidemics have features of both common-source epidemics and propagated epidemics.

- The pattern of a common-source outbreak followed by secondary person-to-person spread is not uncommon.

- These are called mixed epidemics.

Response to Epidemics

- Experts suggest that the best way to prepare for an epidemic is to have a disease surveillance system.

- Be able to quickly dispatch emergency workers, especially local-based emergency workers,

- Have a legitimate way to guarantee the safety and health of health workers

- Create awareness

- Advocate effective action

- Social mobilization based on volunteer activities and logistics support (transport, warehouses, etc).

References

- Park, K. (n.d.). Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine.

- Gordis, L. (2014). Epidemiology (Fifth edition.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

- https://www.who.int/environmental_health_emergencies/disease_outbreaks/en/

- https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section11.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/overwght99.htm.

- https://philpapers.org/archive/ANOWIA.pdf